I write for a number of significant blogs and arts/IP related online news sites:

ARENA

Clubb Troppo (all these articles have been reproduced below in ascending order from earliest to latest)

The Mandarin

‘Of Fire and the Plague’ originally published in ARENA, 4 June 2020

In late December, at the very peak of our region’s fire emergency, somebody rang our Rural Fire Service (RFS) headquarters and complained: ‘Why haven’t you put the fires out?’.

There are parallels between the current pandemic, the recent fire emergency and ‘wildfires and humans’ more generally. Both fire and viruses are expressions of cellular life itself. Plants absorb carbon dioxide, water and trace minerals, and then use sunlight to turn that into twigs and leaves. Heat and dryness turn those twigs and leaves into fuel, and fire then turns that fuel back into carbon dioxide, water and mineral ash. Rain prompts another turn of the great wheel. If there was no plant life, there would be no fire.

Viruses are also an expression of cellular life. Viruses in themselves have no metabolism: they have no energy. Viruses commandeer the metabolism of the cellular life forms that they infect; they turn the metabolism—the energy—of any cell that they infect into the reproduction of that virus. For COVID-19 we are fuel for the fire.

When a wildfire first starts, if you can get in quickly, build containment lines and hit it hard, with luck you can suppress that fire before it has a chance to really get going. But if that chance is lost—if the fire has become many kilometres wide, is spotting miles away and fuel is plentiful and very dry—then attempts at suppression become a foolhardy risk of life as well as a waste of time and energy.

So the strategy changes: evacuate the vulnerable, the impossible to defend. Defend that which can be defended, wait for the fire to burn itself out and pray for rain.

It seems to be the same for pandemics such as COVID-19. Suppression can work if the outbreak is small and you’re quick and have some luck. But if a virus has already spread widely, is spotting even more widely and there is plenty of fuel, attempts at ’broad brush’ suppression are a waste of time and resources and possibly even dangerous.

For example, in response to the pandemic Vietnam acted quickly. The country commenced border restrictions on 1 February 2020 and got on top of small local outbreaks. To date, Vietnam has had zero COVID-19 deaths. The mixed results for nations that did attempt widespread suppression after their ‘fires’ were already too big to contain makes me think that local factors akin to variations in terrain, weather patterns and fuel loads were more important than anything else. For example, in the United Kingdom it appears that too many assets were allocated to the defence of hospitals and too few to the defence of aged-care facilities.

The contrast between the low death toll in Japan, which did not do a nationwide mandated ‘lockdown’, and the much larger death toll in the United Kingdom, which did, is striking. I began to think about the similarities between viruses and wildfire after reading about the stark contrast between the position of Sweden’s health authorities regarding COVID-19 and the positions of the health authorities of most other European nations. I was reminded of a long dispute over how best to approach wildfire that can be caricatured as: ‘all fire is bad fire; it should all be suppressed’, versus ‘some fires are good; we should act to mitigate but not suppress’. One of the things that the two positions have in common is that, historically, in practice, neither approach has ever worked perfectly in Australia. There will always be lightning strikes resulting in the fire that got away on a windy day after a long drought. Equally, doing hazard reduction, cultural burning and the like on the enormous scale needed year after year is not practical, at least not in the populated south-eastern parts of Australia. One such lightning strike hit on the night of 25 November 2019, starting a fire on Black Range about twenty-five kilometres west of the town of Braidwood, New South Wales, where I live. For various reasons the RFS was not able to get to that fire before it was too big to suppress. By Friday 29 November the fire had grown large; it was burning just 8 kilometres from Braidwood, and over the next few days things were touch and go on the outskirts of the town. The view from our front balcony was livid with burnt debris landing everywhere. We watched a DC-10 air tanker drop fire retardant on Jillamatong Hill just 2 kilometres from us. However, the regional RFS was able to deploy a lot of assets to the town’s defence. According to a report from one of the local RFS brigade captains, road graders ran over the paddocks near the fires at ‘40 kph for thirty hours, nonstop’, building containment lines.

By 5 December the town was out of serious danger. In hindsight, Braidwood was fortunate that the fire that most directly threatened it came early and was a relatively cool fire. After it had burnt through the sixty years of fuel load that had accumulated in the great forests just to the west of us, we were, to a degree, immunised from the worst of the fires. Attention then shifted to the vast forested regions and national parks surrounding the settled areas that stretch from Eden to Nowra. The worst of the fire season was yet to come to our region and the adjacent south coast.

By mid-December the conditions were shocking: very hot, no ground moisture, and with dry, hot north- westerly winds. The fires to the east of us, which came to be called ‘the Beast’ started to really get going at the end of the first week of December. We will never forget the first time we saw a pyrocumulonimbus cloud rising about 30 kilometres to the east; it was beautiful and very frightening. I knew that at the base of that cloud, the temperature must be comparable to ground zero in Hiroshima. (A CSIRO report on the Ash Wednesday fires of 1983 estimated that the temperature at Cockatoo in Victoria’s Dandenong Ranges reached 3000 degrees Celsius.) The carnage inflicted by the Beast continued to grow: Lake Conjola, Mogo, Rosedale, the outskirts of Batemans Bay, Moruya and Cobargo, and a murderous New Year’s Eve.

In Braidwood we lived through a time dominated by an all-pervasive smoke stench of burnt flesh; of streets where the only movement was the endless queues of RFS, SES and other emergency-services tankers refuelling, and day after day of asking: Northangera Rd, Back Creek Rd, Charleys Forest, Farringdon, Monga, Mongarlowe, Araluen, Krawarree and so on—did they get through today?

As the long days of unrelenting 40-plus-degree heat with very strong north-westerly winds set in, I kept thinking, ‘I’m glad that the big forests to our west burnt out when it was still cool and the winds were so much weaker.’

Returning to the analogy between the fires and the virus, something makes me uneasy about Australia’s success in suppressing COVID-19 to date. In Australia we have no ‘herd immunity’: we still have plenty of ‘fuel’ for the virus to burn. The virus is still smouldering, largely stifled, in Australia, and actively burning in many other places around the world. Embers will continue to land here, and we have already gone through a lot of our resources and assets. Meanwhile, life is thoroughly disrupted, and unemployment, recession and austerity are all set to intensify, reducing our ability to respond. I don’t know what kinds of strategies we should follow when this virus or the next pandemic inevitably flares up again, but I am certain that a rigid, one-size-fits-all strategy is not the way to deal with either wildfires or pandemics. We need to take an approach akin to cultural burning: more nuanced, responsive to local terrain and conditions, adaptive to circumstance, and flexible.

ENDS

Originally published in The Mandarin, 5 December 2016

Artists’ scheme: a good idea at the time, till it dodged own appraisal

Authors: John R Walker and Nicholas Gruen. John R Walker is a practicing visual artist and Nicholas Gruen is the CEO of Lateral Economics.

Not every policy will have the intended outcome, but we can respectfully evaluate what went wrong and learn from it. A stakeholder and an economist look back at an arts policy where the evaluation was buried.

It is six years since Australia’s Artist Resale Royalty scheme (ARR) commenced and three years since submissions to its Post Implementation Review (PIR) closed, though the review itself has never been published. However, in the absence of a healthier public commitment to transparency, we can now answer some questions about the scheme.

How much has the ARR helped artists?

Supported, both at its inception and since, largely for its assistance to Indigenous artists, the ARR has delivered approximately $1.6 million to Indigenous artists, or about $260,000 per year according to Copyright Agency (CAL), which manages the scheme. Over the last six years about 420 non-Indigenous artists — about 5% of the total of around 9000 professional non-Indigenous Australian visual artists — have received around $2.6 million in royalty payments averaging $430,000 per year.

Of the total number of individual ARR royalty payments made to date, 41% have been between $50 and $99 (minus the 15% management fee). However, because so many artists commanding the highest prices are dead, 168 estates have received 45% (around $1.9 million) of all ARR’s payments. This compares with government payments to the start-up and administration costs of the ARR of $2.2 million.

Does the scheme generate more benefits than costs?

If this result looks woeful to you, it does to us too. Alas it’s just the beginning. The bare facts already reported demonstrate the extraordinary inefficiency of the program. But there’s more. Brian Tucker Accounting, which services many Indigenous art trading businesses, offered this in its submission to the Post Implementation Review of the ARR scheme:

“I know more than one gallery that has gone through up to three bookkeepers, and we have actually had to send in a fully qualified accountant to do bookkeeping work, unpicking and correcting entries.”

But the ARR looks worse than merely wasteful. Its net impact on artists’ total income is probably negative. Because most artists either get nothing from the ARR, or at best get an occasional small payment, it only needs to have a small overall negative impact on artists’ sales for its costs to exceed its benefits.

In 2004, Access Economics was commissioned to model the likely impact of an Artist Resale Royalty. It warned that claims of net benefit to artists were based upon “extremely unrealistic assumptions, in particular the assumption that seller and buyer behaviour would be completely unaffected by the introduction”. Access Economics concluded that those claims were both unhelpful and potentially misleading.

A 5% royalty may not sound like much, but the various intermediaries that make the art world go round live or die not by the absolute prices charged but by the margin between purchases (or consignments) and sales. Meanwhile the ARR is calculated on the total sale price.

Consider the practice of John R Walker — co-author of this article. Say his works sell for $10,000, netting him $6000 after the 40% margin for costs. If the ARR was, through buyer nervousness, to cause him to lose just one such sale, he’d need the resale royalties due on $120,000 of future re-sales to recover his losses. This is before accounting, administration and compliance costs which, it seems reasonable to assume, must be at least equal to the amount the copyright collecting society CAL charges to cover its administrative costs which is 15% of the revenue it collects from the royalty.

Falling sales and the ARR

The past six years has seen a huge fall in the value of sales of Australian art, particularly Indigenous art, through Indigenous art centres — ORIC’s At the Heart of Art report, and Acker and Woodhouse’s The Art Economies Value Chain all show overall drops of around 50% in art centres’ sales income. The value of auction sales of Indigenous art has dropped by 60-80%. And the total value of auction sales of all Australian art has also seen significant declines.

There are undoubtedly many factors behind this decline in Australian art sales. On the other hand the ARR seems to have had an appreciable effect. Eminent artist Ben Quilty offered this in his submission to the Post Implementation Review of the ARR:

“I had spoken to some very serious collectors (including one of this country’s biggest collectors of Indigenous art, who I have asked to submit to this review) and many showed concern that their purchase of an emerging artist’s work could lead to a resale royalty, on top of the resale commission of galleries and auction houses at the point of resale … Purchasers are confused by the possibility of future royalties owed by them and therefore it is reasonable to say that those sales have been directly affected in a negative way.”

Note that artists who judge the ARR to be against their interests have no right to opt-out.

All this has been done with magisterial high-handedness. The ARR was one of the few pieces of regulation for which no Regulatory Impact Statement was done in 2008-09. A post implementation review was conducted in 2013 but it remains hidden away from the public’s prying eyes. It is increasingly obvious that the Ministry for the Arts won’t acknowledge the obvious — that the ARR was a nice idea but, as Access Economics warned, never made practical sense. And as CAL boasts about the scheme, and its ever rising revenue, the Ministry for the Arts would prefer we didn’t talk about it — ever.

ENDS

Originally published in Art-Antiques-Design.Com, 29 July 2015

Artist’s Resale Royalty in Australia – Strong evidence of a catastrophic decline in both sales and prices

In this article, I shall give an overview of the highly corrosive impact, which the Artist’s Resale Royalty (ARR) has had, and is having, on Australia’s art market. The impact of ARR also appears to have had an entirely adverse reaction on the UK’s art market; with trade in a large proportion of valuable secondary market art works now, quite obviously, taking flight to places like New York, Switzerland and Miami. Below, as you will see, many reputable and governmental sources have been cited. Due to the implementation of this scheme, we, in Australia, have sadly seen our indigenous art sector virtually wither away right in front of our eyes since the ARR was introduced back in 2010. I’m an Australian artist; I’m not being paid to write this, and what follows is an honest appraisal of what we are facing here due to the ARR. It is based on my personal experience and on factual publicly available information.

ARR percentage rates vary depending on countries, but here in Australia, the rate stands at 5%. The impact of this apparently small charge -‘just 5%’- on the more average resale, is much greater than it might first seem to be. Because the ARR is 5% of the gross sale price, and not 5% of the net profit, the royalty payment often consumes 60% or more of the net profit on an eventual secondary market resale. For example, if an artwork is purchased for $100,000, and is resold for $120,000 with the costs of sale were totalling $10,000, then the royalty due @ 5% of $120,000 is $6000, which is 60% of the net $10,000 profit on that resale. And this calculation, like the ARR itself, makes no allowance for inflation. In reality, the royalty can actually be all or more of the net profit on the more average resale. As in most parts of the world, the ARR is also due on losses made. If that same artwork was eventually resold at a loss for say $90,000, then the royalty @ 5% ($4,500) is still due.

It gets stranger.

The primary market and the resale (secondary) markets are connected. Art resale prices are, naturally, a factor in first sale purchase decisions. Here is a quote from a submission to the Australian Federal Government from the late William Wright AM:

“At meetings I have attended at the Australia Council [of the Arts] for the purpose of discussing this [the ARR] scheme it has been repeatedly asserted by administrators present (without a shred of market knowledge or substantiation) that the royalty will bring increased income into the art market: when it is apodictically clear to all who are actually part of the merchandising and marketing areas of the visual arts industry that it can only have the opposite effect.“

Depressed resale prices and declines in the total value of the Australian market for art are bad for artists, first sale prices, net value of sales, and for patrons of the arts, who do, after all, provide the supply of money into the market. As an artist who continually produces work, I’m pleased if a client or a gallery sees an increase in the value of works. Isn’t this what we might call a win-win situation? The best way by far of supporting artists’ careers in the long-term is to encourage a healthy buoyant free market, for all art.

Bill Wright’s words remain unarguably true. Adding a punitive, arbitrary requirement that collectors pay back 5% of the gross resale price, with no regard to profit and loss or even inflation, is severely handicapping the chances of artists selling their artwork in the first place. This has certainly been my experience since the introduction of ARR, as my accountant can attest.

A number of representative gallerists and accountants, who between them represent a large cross section of Australia’s professional artists, in private and in general terms, all say that since 2010, the year of the ARRs introduction, there has been an across-the-board decline of artist sales income, to the tune of between 35% and 50%, and in some cases, worse. Most advocates of the ARR scheme dismiss this decline in sales as a consequence of the Global Financial Crisis back in 2008.

It gets even stranger, really it does.

There is good evidence from other discretionary purchase markets, such as luxury cars, that the long-lasting decline in artists’ sales incomes is not simply the result of a general downturn in the market for discretionary goods. More tellingly, detailed research in the UK has shown that, in the past few years, the UK market for modern and contemporary art – the area directly impacted by ARR – has declined rapidly, whilst the modern and contemporary art market in the USA, for example, has grown, at a rate of about 25% year on year for the same period. The UK’s art market for long dead artists unaffected by ARR, in comparison, has remained steady and shown modest growth. This would indicate that the segment of the UK’s art market directly affected by its version of ARR, has, quite simply, fallen off a cliff. Think about it, when was the last time you heard of a £160m Picasso selling in the UK?

Quite obviously, this contraction in the UK art market has had a knock on effect concerning employment and job creation in the UK’s art market, as it has here in Australia. In fact, the whole basis for the EU’s ARR Directive (1996) was exactly that the presence of ARR in some EU member markets and not in others was causing art sales to relocate to non-ARR markets within the European single market. Therefore, if sales are not being diverted to ‘non ARR’ markets by the ARR, then the EU’s primary justification for imposing ARR on the UK market, and by implication the justification for their campaign to impose ARR on the rest of the world, is quite simply not valid.

We all understand that ARR is ‘good intentioned‘, but the fact of the matter is that in its present form, it’s a bad scheme, which in Australia, will hopefully not last for much longer.

Back to Oz, and Superannuation Funds.

The concomitant introduction of the ARR in Australia along with the changes to art in Self Managed Superannuation Funds (SMSF) rules has had a particularly savage impact upon the sales and reputations of indigenous art and artists. In terms of localized artistic economies, in 2010 in the major tourist town of Broome, there were ten businesses dealing in indigenous art. Now, in 2015, there is only one remaining, and the Short St. Gallery can be quoted as saying “we have gone from investing $2million per annum in indigenous art, to just $200,000 per annum.” Anecdotally, commercial art galleries in Western Australia are heading towards virtual extinction.

Experience has shown that artists, myself included, since June 2010 sales of artworks valued above $30,000 have become rarer when compared to sales in the years prior to the introduction of ARR. Speaking with a number of patrons and collectors, the response is always the same when discussing ARR; that it is a discouragement to buying art in the primary market, and in particular, to the purchase of the more costly works. In one conversation, a close patron said, “what if my wife needed emergency treatment and I needed to cash that artwork in, what are re-sales like?” This is not an insignificant consideration when considering a purchase. What would you say?

Some of you may know of the artist Ben Quilty? He recently had a solo exhibition in London at the Saatchi Gallery, and is an Archibald Prize winner here in Australia, a bit of an Ozzy icon, if you like. In his submission to the ongoing ARR Post implementation Review, he stated:

“I also voiced my concern to The National Association for the Visual Arts that a Resale Royalty Scheme would risk support for the emerging sector of the Visual Arts. I had spoken to some very serious collectors (including one of this country’s biggest collectors of Indigenous Art – who I have asked to submit to this review) and many showed concern that their purchase of an emerging artist’s work could lead to a resale royalty, on top of the resale commission of galleries and auction houses at the point of resale.”

The ARR was presented to the Australian public as primarily a scheme aimed to benefit Australia’s indigenous artists. The effects of the ARR have, in practice, turned out to be diametrically opposed to this aim.

LET’S CRUNCH SOME NUMBERS

The Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) is the appointed manager of the Australian ARR scheme. Figures published by CAL on their website show that 60% of the total value of the ARR royalty money paid to date, has gone to non-indigenous artists and their estates. The total value of indigenous art sold at auction in 2014 was $5.6 million, an 80% drop in sales since 2007, (source john Furphy’s Australian auction sales digest) and this decline in indigenous art sales in general, really took off after the implementation of ARR, in 2010.

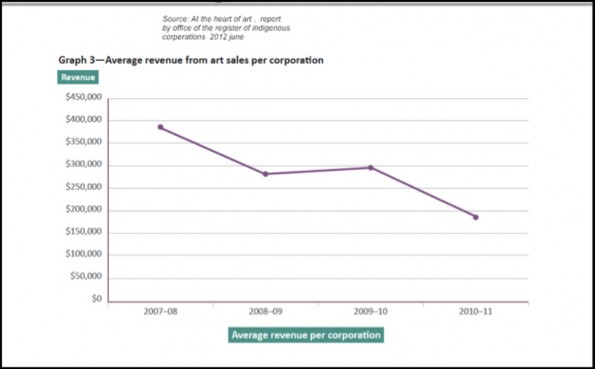

The Office of the Register of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) 2012 report, At the Heart of Art: A snapshot of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations in the visual arts sector, has a graph of the indigenous arts centers average sales income that covers the period prior to and after the introduction of the ARR scheme and the art in superannuation funds rules. This chart shows clearly that the Global Financial Crisis did cause a drop in sales; however, the chart reveals that in the following year sales leveled out and showed signs of re-growth. In the year 2010-11, the year of ARR introduction, sales again contracted.

Given enough time, the proportion of ARR value going to indigenous artists and their estates must decline to about 10% (or less) of the total value of the royalty payments made. If indigenous art re-sales are 5% of the total value of the affected market, then the royalty payments to indigenous artists will be 5% of the total value of royalties paid. The combined value of the top three largest individual royalty payments to date is $147,000, which is $31,000 more than the total value of all of the bottom 2,000 individual royalty payments combined, as given by the Department of the Arts in answers to Questions on Notice by Senator Gary Humphries in February 2013. None of the 3 recipients of those 3 largest individual royalty payments were indigenous and only one of them was alive, at the time of payment.

A number of more recent art economic studies of the indigenous art sector by Acker and Woodhead show a sector in continuing deep trouble. They report that many of the arts centers are, on current trends, heading for insolvency, and that income from sales is stagnant. For more than half of these centers, government funding now, significantly, represents more than 50% of their total income.

Professor Jon Altman has also raised the serious issue that a significant proportion of the public funding to the operating costs of the ARR scheme has come from indigenous specific funds within the Department of the Arts, even though the scheme is clearly not an indigenous specific program. Altman reports that the highly respected Australian Indigenous artist John Mawandjul, has gone from being an internationally celebrated and revered income-generating artist, to retraining as a tyre repairman.

He goes on to report that most of the great ‘bark’ painters at Maningrida have simply stopped producing art.

A quote below:

“Last month he told me he had given up painting, I watched him aged over 60 going to the Ye Ya workshop in Maningrida looking for a ‘real job’ as a tyre repairer, as required by the new Remote Jobs and Community Program if one is not to be breached and left destitute.”

Eminent Indigenous Australian Artist, John MawandjulImage Courtesy: Art Gallery New South Wales

Essentially, resale royalties are a restraint of trade and must, and have, resulted in reduced prices and reduced overall value of any market, which they apply to. Buying art that is affected by resale royalties is, of course, not compulsory. However, being part of the ARR scheme for contemporary artists in Australia is compulsory.

A percentage of buyers in Australia have shifted to other forms of art and / or investments that are not penalized by a royalty that does not allow for costs, losses or inflation. ARR is undoubtedly a restriction on artists’ rights of free contract, which has raised real, and harmful market distortions and substitution issues for many of the artists affected by the scheme. Why can’t we sell our art without the ARR provision, for a better first sale price?

The option of opting in to the scheme is simply not available. How can it be that we, as artists, have no choice in the matter, and that we have mandatorily been roped in as part of this corrosive scheme? Opting out, on a limited case-by-case basis, is of course an available option, but hang on a minute, isn’t that the wrong way round? I happen to like my rights, and I am perfectly capable of making a decision on whether I wish to opt in to a scheme available to visual artists. With this particular scheme it should also be noted, that the vast majority of artists do not have re-sales of any consequence at all, especially while we are alive.

There is no way that a restriction of artists’ rights of free contract could be construed as an inalienable i.e. compulsory individual economic right of artists. All restraints of trade must reduce, and in the case of the Australian Art market, seriously damage both prices, and the market.

I have discussed this matter at length with Professor Paul Frijters, one of Australia’s more eminent economists at the University of Queensland. In his opinion, and in a perfect frictionless market, the royalty would simply reduce the value of the market “by 5% for every time that an artwork gets sold: if buyers expect art to get resold 4 times in their life, the prices would drop some 20%.”

He went on to say, “the added costs also directly depress prices. The royalty is more likely to reduce prices by factors of up to 50%, depending on the frequency of trading in the artworks affected.” As it happens, frequency of trading in the artworks affected, was much higher in the Indigenous art sector than other areas of Australia’s artistic offerings.

IN CONCLUSION

Both the lived experience and the ‘101’ basic economics of ARR in its current form, show it to be a very bad idea if you are trying to make and sell art for living, or if you are interested in supporting art and the artists who create. Additional layers of collective bureaucracy, and bigger Government, have never worked in favour of business.

Buying upfront, and then on-selling of indigenous art was the principal business model for indigenous art sales prior to the introduction of ARR. Since then, indigenous sales, prices and volumes have plummeted by at least 50%, with some estimating a more realistic number being in the region of 80%.

In addition, there is overwhelming evidence, that the scheme supports the larger already established artists, with an emerging marketplace seeing little, or no benefit to the scheme. How can it benefit or add value? Emerging artists simply don’t have re-sales.

The Australian ARR scheme is currently the subject of a Post Implementation Review (PIR). Hopefully this ‘good intentioned‘ but bad in reality scheme will not last much longer.

ENDS

The following posts are in ascending chronological order: oldest to most recent.

They include the extensive discussion about the Artist Resale Royalty legislation, the changes to the SMSF superannuation rules and commentary on the review of the Artist Resale Royalty scheme.

ARTIST PROFILE Magazine – Blog

John R Walker responds to Joe Frost’s article “Bad words and thoughts”, Issue 12:

August 20th, 2010 by Owen Craven | Filed under Letters.

John R Walker, Work bench, Ian’s shed, gouache on archival paper, 2010

IN HIS ARTICLE “Bad words and thoughts” in ARTIST PROFILE Issue 12, 2010, Joe Frost writes about the many paradoxical ways of using the term ’modern’. You can have a fair bit of fun with ‘modern’: ‘that Swedish moderne chair looks perfect in your very contemporary 1950s retro-look lounge room’. Most of the time we manage the conflicting usages of terms such as ‘modern’, ‘contemporary’ and ‘advanced’ pretty well. Most of us do not automatically assume that the latest model is best. We pick and choose; a bit of the latest and a bit of the classic.

If you Google “The Battle of the Books” you will find pages of essays, discussions, references and citations. “The Battle of the Books” is one of the sharpest writings on the fight between the classic canon and contemporary writing, and it was first published in 1706! The language and style of Jonathon Swift, the author, is very modern. The episode of South Park in which Mr Man introduced Paris Hilton to the ‘fundamentals of life ‘ (he shoved her up his arse) was very ‘Swiftian’.[1] The Swiftian irony about battles in learning libraries between contemporary authors and classic canon authors is just that: nothing new.

During the 1960s and 1970s, art education developed a widespread and profound confusion about usages of terms such as ‘new’ and ‘original’. A good example concerned the confusion centred upon conflicting usages of the term ‘advanced’. ‘Advanced’ is a term that can have usages that are time or spatially specific: ‘that car has advanced down the road’. It can also have meanings that are perceived qualities: ‘That car was very advanced for its day’. The confusion at that time about terms like ‘advanced art’ and ‘modern art’ had serious effects that have lasted to this day. At the time there was a widespread, innocent desire to create art that did not yet exist and ironically, this innocent desire was to a degree successful: contemporary art became a bit hard to see. This confusion led to a general and fairly extreme rejection in education of the very idea of a ‘classic canon’ and, in particular, for artists’ education, this led to a rejection of ‘copying from the masters’.

Steven Jay Gould was an evolutionary biologist who was very sharp on the vital difference between evidence of directional changes in time: that is, history, and evidence of qualities such as improvement or progress. In both evolution and history, progress (unlike change) is not at all inevitable. Gould wrote an essay on the themes of “The Battle of the Books”, the canon and changes then happening in education. In his concluding observation, he stated that:

“I am worried that people with an inadequate knowledge of the history and literature of their culture will ultimately becomeentirely self-referential, like science fiction’s most telling symbol, the happy fool who lives in the one dimensional world of pointland, and thinks he knows everything because he forms his entire universe.”

Gould continued:

“I can’t do much with a student that doesn’t know multivariate statistics and the logic of natural selection; but I cannot make a good scientist – though I can forge an adequate technocrat – from a person who never reads beyond the professional journals of his own field” [my italics][2]

If this is true for anybody who wants to be good at science, it is then doubly true for an artist who wants to be good at art. Contemporary education and training has become too compartmentalised, jargon ridden and too narrowly ‘professional’ in focus. A wide knowledge of what used to be called the ‘liberal arts’ is very useful to any creative enterprise.

In the visual arts, the idea of ‘copying for education’ was largely abandoned. Quoting something is not the same as ‘copying for education’ by which I mean, re-producing the act of making something.[3]

Years ago, Douglas Hofstadter rightly stated that “all originality is variations on a theme”.[4] Error prone copying combined with the survival of the fittest is the basis of all evolution. Whilst it is obvious that slavish copying ends in stasis, it is not so obvious that no copying also ends in stasis. Paradoxically without copying, that is, re-producing, there can be no ‘meta’ (change).

The concept or idea of an art without antecedents is a concept of evolution without origins. This is a sort of religious (teleological) conception that, when transposed into art education had effects that were often illogical, strangely circular and sometimes harmful.[5] An art training that cannot learn from history, creates artists that are stuck in a show called groundhog day.

[1] Swift’s solution to the starving Irish problem was ‘eat babies’: “I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled …”. From his essay “A modest proposal” 1729.

[2] The essay, ‘Sweetness and light’ is published in a volume of Gould’s essays entitled Dinosaur in a Haystack.

[3] Auden believed that the best way to understand a poem was to physically rewrite it, line by line.

[4] Gödel, Escher, Bach (usually called GEB) is a book by Douglas Hofstadter. It is a meditation on the strangeness that is ‘representation of representations’.

[5] The not-yet-existent future affecting the present is a ‘Terminator’ sort of idea.

ENDS

‘With friends like this’: Labor policies and the commercial, independent visual arts sector

In June and July of 2010 the Labor government launched two policies directed at the commercial visual arts sector. These policies are hurtful, contradictory, confused and confusing. While it is almost impossible to get unanimity on anything from the independent, commercial sector, the government has surely achieved a first. When the question is asked “why is the government doing this?” the unanimous answer is “they must really hate us”. Let‘s start with the Australian Resale Royalty Scheme which started life on June 9 2010. Passage of the act was uncontroversial and there was a bi-partisan hope that the scheme would somehow deal with the problem of remote indigenous artists selling their art, in ignorance of its real current market value, to unscrupulous carpetbaggers. On the whole, both the Act and its technical implementation has been done as well as it could be.

Sadly there is a paradox at the heart of this scheme.

For what seemed on the surface a generous intention to improve the lot of indigenous artists has actually had the unintended consequence of complicating the first sale of their works; in some cases actually reducing the prices at which their works are sold and, worst of all, reducing demand for their works. Certain figures tell a story. The scheme so far has delivered $600,000 to artists (60% of which went to indigenous artists), yet in the same period the government has had to commit a total of $2.25 million to run the scheme. If inefficiency was the worst outcome of the scheme that would be a poor result, however the consequences go well beyond the cost / benefit equation. The scheme is distorting the art market itself and this result is reducing the amount of money that artists can earn from the sale of their work. It has created market distortions that are bad news for most working Australian artists.

Access Economics warned that the claim of net benefit to artists was: “based upon extremely unrealistic assumptions, in particular the assumption that seller and buyer behavior would be completely unaffected by the introduction of RRR [ARR]”

I will detail the way in which this has been achieved later in this piece but I want to point out that this unintended harm should not be news as it was anticipated by a respected Canberra-based economic consultancy. In 2004, Access Economics was commissioned to model the likely impact of an Artist Resale Royalty. In their report, Access Economics warned that the claim of net benefit to artists was: “based upon extremely unrealistic assumptions, in particular the assumption that seller and buyer behavior would be completely unaffected by the introduction of RRR [ARR]” and that, “Access Economics considers that the results of this analysis are both unhelpful and potentially misleading”.

Access Economics has been proved correct.

Following are the five main reasons why the resale royalty scheme has been counter- productive, particularly towards the very indigenous artists it was supposed to assist.

1. Buyers face a clear choice between investing in art that is affected, or art that is not affected. A percentage of buyers are choosing to not buy at all, switch to unaffected types of collectables such as ming porcelain or they are adjusting their offering price on first sale down to reflect the royalty to be paid on resale. The scheme is a hobbling of the competitiveness of artists affected by the royalty , particularly so in the case of indigenous artists.

The following figures are revealing. Resales of indigenous art at auction are in marked decline: last year’s auction sales totaled only $8 million (the lowest this century!), less than 10% of the total art resale auction market. Yet 60% of the value of resale royalties collected was paid to indigenous artists. The answer to this paradox is that many of the resale royalty payments that indigenous artists are receiving are in reality delayed payments for first sales, less costs. Uniquely, the indigenous market is an area where artworks are regularly bought from artists on a paid-in-full, up-front basis and then onsold. Because many indigenous artists sell their work on this wholesale-retail model, these artists have simply seen a reduction in their wholesale (the first sale) prices that matches or exceeds the royalties they eventually receive on the subsequent retail sale.

2. There are aspects of the scheme that are especially problematic for indigenous artists. The Royalty makes no allowance for costs. The costs of bringing art from the remote communities to market are higher than those for much of the rest of the Australian art market. The lack of allowance for marketing costs is a particular disincentive to investment in the marketing of indigenous art.

3. Reducing the resale market affects the primary market. A healthy art resale market is good news for artists’ first sales. If one of my paintings was to resell for much more than it was first sold, it is great news for me: it is a great sales pitch for more first sales and it raises the value of my back catalogue.

The effects of this anxiety have been particularly marked in indigenous art: drops of more than 50% in prices for some blue chip indigenous artists have occurred since the royalty’s introduction.

4. The biggest single negative of the Royalty scheme is the effect it has had on buyer confidence and buyer numbers. The hit to the market’s confidence derives mostly from the fact that: (a) it had little broad community support or need; (b) it was done without proper consultation; it took most in the sector by almost complete surprise; (c) the scheme was imposed by law hence, the scheme looks like government anti-market interference simply for the sake of it. Therefore, the scheme in itself has created an anxiety that the government has something in principle against buying and selling art. A percentage of buyers have simply decided that it is “all too hard” and have left the field altogether. The effects of this anxiety have been particularly marked in indigenous art: drops of more than 50% in prices for some blue chip indigenous artists have occurred since the royalty’s introduction. These drops in price greatly exceed the effects of the GFC on the non-indigenous art sector prices.

5. The scheme is an exemplar of the adage that special cases make bad law. Its effects are widespread, yet the problems it sought to address are isolated.

The perverse effect of the resale royalty on confidence and demand were set to be made far worse by the next Government policy announcement on July 10th 2010.

The resale royalty scheme now entered into a particularly bad marriage with the government’s changes to the rules which govern the purchase, storage and sale of art to Self Managed Super Funds (SMSF). The result is that the anxiety caused by the impact of the resale royalty has connected with a bigger and mounting anxiety about the effects of the government’s new restrictions on SMSF art collections, particularly as it applies to pre-existing collections.

“[T]he panel did not take the art sector’s concerns into consideration because its task was to review the superannuation industry and not all the industries around it”.

The genesis of the changes to art investment rules by SMSFs date from June 2010 when the Government released the Report of the Cooper Inquiry into Superannuation. It contained a bombshell, recommending that art be wiped entirely from all SMSFs. When asked why the enquiry had not consulted with the art sector, Cooper Review panelist Meg Heffron was reported as saying that, “the panel did not take the art sector’s concerns into consideration because its task was to review the superannuation industry and not all the industries around it”. Many were shocked by the fact that the then Arts Minister Peter Garrett knew nothing about the impact of the Cooper recommendation on art.

Labor was soon confronted with angry demonstrations by leading artists in a seat that was vulnerable to the Greens (previously safe Labor heartland occupied by outgoing Lindsay Tanner) According to a number of commentators including Marcus Westbury writing in The Age, Labor was faced with a real possibility of losing the seat of Melbourne because of anger over the damage that the Cooper recommendations would do. The Greens quickly condemned the Cooper recommendations and further condemnation ranged across the whole political spectrum from Katrina Strickland in the AFR and Michaela Boland in The Australian. About three weeks before the election date, Labor announced that it would reconsider the recommendations. Marcus Westbury in The Age, 22 September 2010 wrote: “Until defused in the last few weeks, the role of art under the Cooper superannuation review threatened to boil over into a full-blown election revolt.”

After the election, the results of the government’s ‘defusing ‘ of the Cooper recommendations were released. It turned out to be spin. Instead of the open ban on art in SMSFs, the government opted for: you can keep art in your SMSF as long as it costs you significant annual fees and you must not look at it; you must not derive pleasure from your SMSF art investment. More importantly, these new rules apply to pre-existing collections. Pre-existing collections have only 4 years to be either sold or moved to off-site, fully and separately insured, climate-controlled storage. This is a costly, onerous requirement. Art accountant Michael Fox estimates the annual storage costs to be between 2 to 5 per cent of the value of a collection. After 10 years this would add up to between 20% and 50% of the value of the collection. Most collections will be sold: for many there is no real choice.

The negatives, contradictions and harm of the two policies are multiplying in unpredictable ways.

1. Capital losses from the sales of artworks cannot be offset against capital gains from the disposal of other asset classes like shares and real estate. This contradicts the ARR scheme that provides a definition of artwork as a category of investment capable of being levied. However, the super art laws do not use the ARR definition of artwork and instead use the Income Tax Assessment Act definition with the effect of denying the capital loss relief on the sale of collections. Talk about having your cake and eating it too! This contradictory treatment of capital loss relief is central to understanding how the cross-purposes of the RR and super art laws have created a real feeling that the commercial art sector has been targeted for political reasons.

The resale royalty scheme is a levy on the value of the resale market. Obviously, the long-term viability of any resale scheme is predicated on a healthy resale market and yet the new SMSF policy is significantly reducing the net value of the indigenous resale market in a long-term way. In the words of Damian Hackett of auction house Deutscher and Hackett: “in the past, I’d estimate that invoices made to Super Funds could reach 10 – 15% of auction sales, with many more bidders registered under SMSFs. We now have zero. This is especially relevant to Aboriginal art.”

As is evident from these figures the super fund investment in art was, in reality, relatively small beer, harmed no one and gave support to indigenous culture. Again, this government policy on art and super looks political in motive rather than economically rational.

2 The rationale behind restricting the acquisition of artworks for SMSFs was that there was excessive growth in holdings of artworks. This was based upon risible estimates by the ATO. Incredibly, the estimates show total holdings of artworks and collectables increasing from $554 million in March 2010 to $678 million in March 2012. This is a more that 20% increase at exactly the period when purchasing art for SMSFs effectively ceased. As is evident from these figures the super fund investment in art was, in reality, relatively small beer, harmed no one and gave support to indigenous culture. Again, this government policy on art and super looks political in motive rather than economically rational.

3 The new SMSF policy has started to create an indigestible glut of indigenous art for resale. The recent 28 May auction of Aboriginal Art from the Superannuation fund of William Nuttall & Annette Reeves only grossed $350,000, well below the estimate range of between $470,000 – $690,000. Mr Nuttall sold his super fund collection because the new rules are “ too onerous and expensive“. This high quality collection was built up over decades by a respected, very knowledgable long-term dealer (Niagara Galleries, Melbourne) and is just the tip of the iceberg. The total value of indigenous art resales at auction in 2011 was only $8 million (the lowest this century). Obviously the total value of indigenous art that the government’s super rules will force onto the market is much more than the art market can cope with. The government is engineering a collapse in indigenous art.

4 Damage to the commercial gallery sector in which artists sell their works is mounting. The West Australian 31 May 2012, reports that three of Perth and Fremantle’s leading representative galleries will be closing and a fourth will cease trading for one year, leaving about 120, one quarter of WA’s high end exhibiting artists, without gallery representation. The effects of the super art ruling is a significant factor in these closures.

5 Minister for Superannuation, Bill Shorten, agreed to an amendment, proposed by the Greens in the Senate, that the new laws would not be enacted if they created a disincentive for super funds to acquire art. For a year now, the government has continued to blather that they are satisfied with the current situation and in that time, the damage continues to mount.

It is not surprising that most in the commercial art sector now firmly believe that this government is hostile and malicious in intention; further, that it is willfully destructive. The super fund tax concessions effectively acted as a support to indigenous art. This tax effective support did create the usual problem of oversupply leading to problems that needed correcting. However, the government removed this support overnight without any provision for a structural adjustment; a thoughtlessly cruel move. The combination of favorable investment status and the special nature of indigenous culture led many investors to assume that support for indigenous art was a safe, conservative investment akin to investing in a government cultural bond. The sudden requirement to either sell (with incurred costs of about 20%) or to store it at cumulative 10 years’ costs of between 20-50% of the value of a collection, without any provision for compensation or allowance for offsetting losses, is unjust. And, one month after introducing the resale royalty scheme, the government acted to greatly reduce the value of the resale market; a myopic move.

In February 2011, Minister Shorten agreed to a Greens amendment that called on the government to: “ensure that any conditions do not act as a disincentive for DIY superannuation funds to invest in Australian art. (General Business notice of motion no.167)”. The evidence that government policies are causing serious harm to the commercial art sector is irrefutable, yet the government does nothing about its promise. It is little wonder that most people in the commercial visual arts sector view this government’s refusal to act on a promise made at election and a promise made to parliament as intentional.

The government’s twinned policies have damaged confidence, reduced tax collections, reduced incomes, made the long-term viability of the government’s own resale royalty scheme more implausible and these policies are threatening to impose a damaging oversupply on the art market. They are costing artists, investors and the government alike. With friends like this, who needs enemies.

Post Scriptum

I have no professional or private involvement in the resale of art. Sales to SMSFs were not a significant source of income for me.

If anything Access Economics underestimated the intrinsic net negative effects on working artists of any resale royalties. The harm caused by such schemes takes the form of what doesn’t happen, and therefore the harm done is often not seen. When an artist, like me, sells a work for $10,000, I pay $4,000 to the costs of sales and marketing (through my representative agent) and retain $6,000 as income. In the case of a $10,000 resale, I would receive $500 (minus costs). If buyer nervousness about the resale royalty was to cause me to lose just one $10,000 first sale buyer, I would need the royalty payable on a total of $120,000 of future resales, just to recoup the lost income of that one primary market buyer.

An insightful paper, ‘Joining the Dots: the sustainability of the Aboriginal art market’, which addresses some of the deeper structural problems of the indigenous art sector, provides good background reading for those interested.

ENDS

‘With friends like this’…. Part II

My previous post – ‘With friends like this’: Labor policies and the commercial, independent visual arts sector– was kindly posted by Ken Parish, 6 June. This piece posted 14 June 2012 on Club Troppo.

In many ways, artist resale royalties are intrinsically a throwback to the pre-reform days of the 1970s and ’80s.

The royalty is both punitive and market distorting in design. For example: A collector buys a painting for $10,000. After some years the collector re-sells that painting for $11,000 gaining a profit of $1000; the 5% royalty on this resale being $550 or 55% of the profit on that resale. If this painting was instead to resell for $9000, a loss of $1000 on the initial purchase price, there would be an additional loss of $400 in royalty due on that resale, bringing the total loss to $1,400.

The royalty does not apply to non-Australian artists; it does not apply to Australian artists who have died 70 or more years ago and it does not apply to many other forms of art-like collectables such as Ming porcelain and non-art furniture. The artist resale royalty is a serious deterrent to purchasing art by living Australian artists.

In 2008-09, DEWHA was assessed as non-compliant by the Office of Best Practice Regulation for the Resale Royalty Right for Visual Artists Act 2009 and a post-implementation review was required to commence within one to two years of implementation. However, the Act’s compliance with the post-implementation review has been delayed till June 2013. Thus the scheme will have operated for three years without meeting minimum best practice requirements. Best practice involves clear need, clear cost-benefit evidence, avoidance of substitution and unintended market distortions. Given the large costs relative to benefits delivered and the punitive and distorting effects upon the market, it is hard to see how it could ever pass a best-practice test.

The scheme harks back to pre-GST days of non-uniform transaction levies and market-distorting tariffs.

Part III of ‘With friends like this’ Artist resale royalties: a strange loop

ENDS

Artist resale royalties : a strange loop

I once overheard a serious conversation between two curators as to whether the urinal they were looking at was a genuine Duchamp or an unauthorised urinal.

Strange loops involve paradoxes that arise from the mixing up of subject and object. Strange loops endlessly change and yet endlessly return to the same point. In this drawing of a strange loop, the ‘top’ of the stairs is also the ‘bottom’ of the stairs; it is the view point that endlessly oscillates up, down and around.

Artist resale royalties [ARR] involve a lot of subject/object paradoxes. For the purposes of the ARR Act, “artist” becomes a special category of Australians requiring special treatment. At the very same time, in wider usage the terms “artist” and “art” have become so fractured and disparate as to mean nothing in particular. For example, Arts minister Simon Crean is reported as in favour of Ms Trainor and Mr James’s contentious proposal to abolish the strictly defined artform boards such as music and dance [and Visual art]of the Australia Council. Their proposal is based in a contemporary reality: distinct classifications of art (and non-art) are, these days, often an arbitrary and nonsensical basis for government policy.

The ARR Act is a mandated, compulsory restriction of the terms under which some artworks can be sold. ARR imposes restrictions of terms of sale upon some makers of some art-like objects. These restrictions do not (and cannot) apply to many otherwise similar objects. As a classification basis for a restrictive law, restricted to a particular classification of Australians, “art” and “artist” are more arbitrary terms than “blue eyes”. Visual art these days does not need to be original, visible or an object in order to be classified as genuine visual art in an art museum. “Art” can be anything and therefore “art” and “artist” means nothing in particular. I walked out of official “art” years ago. The imposition by Law of a special class “artist” on me is annoying, anachronistic and a strange discrimination, apparently all for my own good.

Who and what Artist Resale Royalties are really for, is definitely a strange loop.

ARRs overwhelmingly benefit successful, mostly dead, artists

In every resale market that has been studied, art resales by value, are always concentrated in the top 20 artists. In the first years of the UK’s resale scheme, 49% by value of the total royalties collected were paid to just 20 artists. And the top 200 best-selling artists account for virtually all the total value of resales. Obviously any royalty on art resales must largely deliver benefits to the handful of artists most favored by the market, 70% of whom are dead artists. It is unbelievable that a very select group of a few hundred people, three-quarters of whom are dead, could have caused a government to pass an Act of Parliament for their benefit.

Australia’s ARR scheme differs markedly from the European resale royalty schemes.

- Australia’s scheme only applies to the subsequent resales of affected artworks purchased after 8 June 2010. (Resales of artworks that have had a change of title after 8 June 2010, i.e. inherited, are also affected.)

- Australia’s ARR allows artists a case-by-case right to not collect or, to make their own collection arrangement (Clauses 22 & 23 of the Act).

- The Act is not part of the Copyright Act: the Act is sui generis (copyright is always opt-in and usage is never compulsory).

- Australia’s scheme is administered by a professionally run agency, properly answerable to government. The tender for ARR was not awarded to the visual artist collection society that for years had lobbied for an EU version of a compulsory resale scheme.

The Australian legislation and management are a real improvement on the lawless schemes exiting in a number of EU countries. However these same improvements give rise to another paradox: a lawful and properly run Resale Royalty Right is pointless.

The EU schemes are in reality an amalgam of hypothecated tax and royalty rights. Given the opposite intentions and purposes of taxes paid to group and royalty rights of individuals, this EU amalgam is intrinsically an impossible mix: a chimera.

In Europe, artist collection societies (and their closely associated peak arts representative organisations) are the largest single beneficiaries of ARR. Collective management is compulsory and therefore support of their collective costs is compulsory. Because these artist collection societies also collect money for an unknown number of artists, mostly dead, unknown or otherwise not contactable, the schemes generate significant revenues that can be redistributed by their twinned artist representative organisations. In parts of Europe there is a long tradition of taxes hypothecated to artist collection societies. Much of the confusion as to ‘who and what’ resale royalties are really for, comes from the conflating of the opposite intentions of individual economic rights and, duties paid to groups. Confusion of individual rights with duties to groups has been so long lasting and so widespread as to be evidence of intention. A limited distribution UNESCO Report of an Inter-Governmental Conference XII/6 Paris, 27 March 2001 reveals the thinking that underlies the EU resale royalties schemes.

Point 20 of the report concludes:

… droit de suite is not an instrument that would considerably improve the economic situation of a country’s artistic population.

The report in point 22 concludes:

in Central European states with a tradition of collective representation not only in respect of the single author’s individual share, but also acknowledging the copyright’s cultural and social role, droit de suite definitely can be one of the different instruments for social or cultural support of the artists. The European authors’ societies maintain social and cultural support organisations also with droit de suite [resale royalty] remuneration.

Unlike dead and uncommonly successful artists, artist collection societies and peak arts representative organisations are definitely in a position to lobby governments. In Australia, lobbying for ARR was largely driven by these Australian groups that are closely intertwined with their EU counterparts. In the words of Australia’s peak artist organisation, the National Association of the Visual Arts (NAVA), in a submission to DCITA in 2004:

for the copyright collection society [Viscopy]… it [ARR] will provide a new area of responsibility and an appropriate level of income for its administrative services.”

In the end their visual artists’ collection society did not win the tender for control of the Australian scheme. Rupert Myer in his Report of the Contemporary Visual Arts and Craft Inquiry of 2002 explicitly ruled out any hypothecated tax-like use of the resale royalty scheme (p.169). Without compulsory and redistributive payments to artist collection societies, resale royalties are simply a circular, phantom representation. How an undoubtedly well-intentioned government was led into adopting the misrepresentation of phantoms as the basis for policy and law-making will be the subject of our next post.

Post scriptum

There is a requirement for a regulatory impact statement before any Australian regulation is introduced. The regulation must meet Office of Best Practice Regulation test as adequate. However,

“In 2008-09, DEWHA was assessed as non-compliant for the Resale Royalty Right for Visual Artists Act 2009 and a post-implementation review is required to commence within one to two years of implementation.”

The post implementation review has been completed and the Act has been given until June 2013 to actually comply with best practice for Australian law making.This means that this ‘sub-prime’ Act will have been operating for three years. During this period it has done real harm to Australian artists and the market within which they operate. Given the conceptual strangeness of the ARR, it would be surprising if it could ever meet normal standards for law-making in Australia.

Our next installment ‘With friends like this’ Part IV:

Our previous posts ‘with friends like this:’ part I here , part II here.

ENDS

‘With friends like this’ Part IV: regulation by the unregulated

This piece posted on 5 July 2012 on Club Troppo.

“In 2008-09, DEWHA was assessed as non-compliant for the Resale Royalty Right for Visual Artists Act 2009 and a post-implementation review is required to commence within one to two years of implementation.”¹

The reason why the Artist Resale Royalty Act was assessed as non-compliant was because the Office for the Arts did not do the required Regulatory Impact Statement. Significant regulatory decisions that are not accompanied by a RIS require a Post-Implementation Review (PIR) to be undertaken within one to two years of implementing the regulatory legislation. And a PIR prepared on this issue will only be assessed as adequate if it meets the requirements in the PIR guidelines.

The reason why the Office for the Arts has not completed and submitted a PIR is because it has not done so. The Office of Best Practice Regulation does not know why the requirement that a PIR be undertaken within one to two years has not been met. The OBPR cannot find any documents detailing why the Office for the Arts has waived the requirement for the Act to undertake a PIR until June 2013, four years after the Act was passed by Parliament .

If there ever was a law that needed an RIS pre-implementation, the Artist Resale Royalties Act 2009 was it.

- The ARR is not opt-in for artists therefore it is not an individual economic right: it is a market regulation mechanism.

- The ARR was intended to regulate unconscionable “carpetbagger’ practices in a section of the indigenous art market. The indigenous art market is about 10% of the value of the total art resale market. 90% of those affected by this regulation are not the intended target of the regulation.²

- The ARR involves significant market distortions and creates real substitution issues. Long dead artists, New Zealand and other non-resident artists are not affected by the regulation. The regulation is effectively a discriminatory tariff against resales of living Australian artists work.

- ARR adversely affects primary market sales: good ‘second hand’ prices for anything that can cost many tens of thousands of dollars is obviously a factor in initial purchase decisions.

- ARR is unlikely to ever pass a cost-benefit test. The administration fee is 10%, therefore the royalties on $100 million of affected resales would only generate $500,000 in administration fees. This scheme can never be self-funding; it will always need government funding.³

- ARR was introduced without any real, wide consultation with those directly affected by it. Given its significant effects upon market and buyer behaviour, this was an unforgivable act.

- The ARR Act is sui-generis; it is not part of the Copyright act. Copyright is never compulsory. Because the Act was not a modification of an existing known system its consequences were and are inherently unpredictable.

- At the level of intention, the ARR is deeply confused as to exactly what its purpose is and who it is for: it is an individual economic right that is semi-compulsory and inalienable; a contradiction in terms. ARR’s benefits to the majority of artists directly affected by it are very questionable; in its 2004 report Access Economics was right to warn that claims of net benefit to artists were based on very unrealistic assumptions about market behaviour.

The other day we had a long conversation with someone at the Office for the Arts. In this conversation, the official repeatedly linked “need” for ARR to a need for regulation of the “unregulated” commercial art market. Claims by the government art sector that the commercial indie art sector needs regulation are so common as to be unremarkable. An hour later we realised that this claim for a need of regulatory power came from a representative of a government office that has not complied with the regulatory requirements of the Office for Best Practice Regulation for almost three years so far !!

Apparently for the Office for the Arts, compliance with internal governance requirements is optional, if it suits. It is the Office for the Arts that is in need of regulation.

Parts 1, 2 and 3 of ‘With friends like this”: With friends like this , With friends like this: Part II , and Artist resale royalties: a strange loop.

¹ www.finance.gov.au/obpr/…08…/bestpracticeregulation0809.pdf

² There are people in remote parts of Australia who live and operate outside regulation, taxes and the law. The problem is not lack of regulation, the problem is the difficulty of enforcement.

³ About $700,000 in royalties has been collected since the scheme was enacted more than two years ago, therefore administration fees so far are about $70,000. The government, to date, has had to commit a total of $2.25 million to implementation of the scheme. And as the scheme gets bigger it will exhibit reverse economies of scale; the collection threshold at $1,000 is well below the economic-to-collect and deliver thresholds.

ENDS

The Governments Review of the Artists Resale Royalty scheme: ‘on Bullshit’ Part I

This piece posted on 8 July 2013 on Club Troppo.

Someone who lies and someone who tells the truth are playing on opposite sides, so to speak, in the same game. Each responds to the facts as he understands them, although the response of the one is guided by the authority of the truth, while the response of the other defies that authority and refuses to meet its demands. The bullshitter ignores these demands altogether. He does not reject the authority of the truth,as the liar does, and oppose himself to it. He pays no attention to it at all. By virtue of this, bullshit is a greater enemy of the truth than lies are.

Harry Frankfurt : “On Bullshit”

The Office Of The Arts (OFTA) is currently conducting a Post Implementation Review (PIR) of its Artists Resale Royalty scheme (ARR). The deadline for submissions to the review is July 12. OFTA’s public discussion paper for this review stinks of ‘ the mushroom treatment’: The discussion paper fudges, omits, and/or attempts to bury information absolutely critical to a proper evaluation of the truth-reality of the ARR scheme and this is not accidental. Any truthful fully informed assessment of the ARR scheme would surely be – Fail.

From Our submission to the review :

The Discussion Paper does not disclose the critical fact that the average transaction cost, for CAL, is $30; $30 is the collection fee due on the $300 royalty payment raised on a $6,000 resale. The current minimum resale threshold is $1,000.

The Discussion Paper does not provide nearly enough information on the breakup by total value of the individual royalty payments. It does not provide the total value of royalty payments of $100 or less, and it does not provide the total value of royalty payments of $300 or less (to $101). The current economic-to-collect-and-deliver royalty payment is $300. The total number of payments below $300 is critical for the evaluation of exactly what percentage of the scheme is operating at below an economic-to-collect-and-deliver threshold.

The Discussion Paper does not explicitly state the median value for royalty payments. It is apparent from the Discussion Paper and the answers to the questions on notice that the median payment value is just above $100. This implies that 50% of the individual payments of the current scheme are well below the economic-to-collect-and-deliver threshold. [the link to Senator Gary Humphries questions on notice is appended below]

The Discussion Paper also does not provide the total value of the top 277 royalties delivered; that is, royalties worth more than $501 each. It is likely that this top 4% of royalty payments will account for much of total value of royalties collected. ARR has wide-ranging effects, is of doubtful viability and its largest benefits in the long run must go to artists who have sold a lot art in the first instance. The ‘why’ of this scheme is questionable.

The gaps in, and inadequacies of, the information contained in the Discussion Paper raise real concerns about the OFTA’s commitment to a transparent and dispassionate evaluation of the scheme. Much critical information needed to undertake a proper evaluation has not been supplied in the Discussion Paper.

Despite the Office For The Arts attempts to fudge, confuse and discourage honest evaluations of its ARR scheme (to say nothing of the ‘unfortunate’, rushed, timing of the reviews announcement), 10 submissions have, so far, been publicly made to the review. Not one of these submissions could be called favorable, several are from artists, and many of the submissions are viscerally damming of the reality of the ARR scheme.

Tomorrow, in Part Two of this post ‘on bullshit and ARR’, we will discuss some of the more damning of the submissions to the PIR of the Artists Resale Royalty scheme, so far – as of midnight today there are just 3 days left for submissions.

ENDS

Review of the Artists Resale Royalty scheme : Part II

This piece posted on 9 July 2013 on Club Troppo.

The adoption of ARR as policy for governments (in about 2002) was driven by a small cluster of publicly funded, ‘arts societies’ management representatives, that were/are closely linked to a global network of copyright collection societies managements. The real aim of these lobbyists for ARR, was always compulsory membership/cross-subsidy of their monopoly society. The introduction of ARR in the form of a compulsory, monopoly management right , would have been a ‘exciting’, ground breaking, precedent for these societies. ARR did not quite turn out the way they wanted, but it has none the less created a lot of damage .

(Next post will be on the ‘phantom employes’ that pushed ARR as policy )

In his 1995 report to the Australian government, renowned IP lawyer Shane Simpson analysed the merits of statutory, compulsory collective, management of copyright (and of ‘neighbouring rights’) versus the merits of voluntary collective management. I quote:

“experience shows that statutory licences drafted without appropriate industry consultation are often unworkable and voluntary licences are required to replace them.”

ARR was introduced without proper wide consultation – especially with individual artists directly involved in the making and selling of their art, their representative galleries and their collectors. Further, the legislation was also brought in without a proper Regulatory Impact Statement [RIS] as required by the government’s own Office of Best Practice Regulation. The result has been pretty much in line with Shane Simpson’s historical knowledge.

Submissions to the Review of the ARR scheme

One of the submissions is particularly revealing of lack of proper consultation, prior to enactment of the scheme. This submission is about a problem that could have very wide ramifications for many exhibiting galleries. Kick Arts, is a Cairns based, not for profit gallery and its problem is: “Our issue has arisen because of the technicality of the title transfer during a sale or return consignment sale under Australian taxation legislation”

In early 2012, after notification by our auditor, KickArts staff were shocked to discover that we had incurred a RRS [ARR] liability in the order of about $10,000 due to the method of consignment sales we used to make primary sales of artworks through our not-for-profit activities. KickArts had made these sales acting in good faith that we were making primary sales, as all sales we make are for stock that has come directly from the artist, their Art Centre, or out of our own printmaking studio where we work collaboratively with the artists to develop the artworks. All artists in these sales have already been paid their agreed artist’s price for these works by us and we never take on secondary market work….

We are concerned, in light of our situation, that there is a potential explosion of liabilities pending in the industry….

Another of the submissions is revealing of just how much damage is being done by the scheme, to artists sales and incomes .

Short St is a Broome WA based Gallery of good reputation. Prior to ARR (June 2010) despite the GFC, there were about 12 galleries trading in Broome. Short St is now the only one left, and it is only just holding on. From Its submission :

It has reduced the number of exhibitions we hold as we can no longer buy works up front that guarantee good enough quality works for shows. Hence it has been very detrimental to the overall marketing and career development of our artists. Also in remote communities some art centres buy works up front then expect the galleries to do the same this means often the painting can incur two lots of resale royalties at its first showing, making it un competitive and forcing artists price of works down. Again harming the very people it was designed to help. The fact it includes GST makes it almost impossible to administer therefore most galleries just no longer do re-sales, this would be for us a reduction of about $250k-500K in sales a year, not including the up front purchases that on average where about $100K so overall for our small business the Re-sale royalty has cost us about $600, 000 a year in lost revenue. It is invasive about our clients details and the $1000 threshold is absolutely ridiculous, as most sales are over $1000 therefore we would need a fulltime staff member to administer and we are struggling to survive. I think the number of galleries in Broome alone has dropped from 12 to one – us, and if the arts legislations that Garrett bought in are not wound back we will close, in fact if this Govt remain, we will cease trading in October, it is no longer worth being in business, and I apologise for ever treating Aboriginal artists as equals it was clearly wrong of me, I should have consulted the Government before I ever did anything for them, and should have realised they were not deserving of independent money and need entire Govt departments to prop them up. I apologise profusely for this oversight……

…There is an awareness and absolute fear amongst the art market and consumers. When it first came out, we received accusatorial and aggressive information implying that we are fundamentally corrupt and that buyers of art are thieves trying to make money on the artists back, and gallerists are such scum that there is no way CAL would ever entrust us to pay our artists the money directly and that they from Sydney are going to develop direct relationships in remote areas with our artists who we have worked with and lived with for 16 years

Last but not least is this submission from Emeritus Professor Peter Pinson OAM , a very widely respected figure in the visual arts and former Head of the School of Art, University of New South Wales College of Fine Arts. In many ways Peter sums up the toxic bullshit that is ARR :

Introducing distortions into the profession.

The royalty tax discourages dealers from practising in the secondary market while doing absolutely nothing to foster the primary market. I came to gallerist practice from (in part) a background in art history. I proposed to represent painters and sculptors who had established their careers in the 1960s and 1970s. I also planned to exhibit secondary market work from this period. A key objective in this vision was to bring attention and appreciation to an art historical period that was currently little-showcased and under-regarded in Australia. My gallery was to be, in part, educational and didactic. Exhibiting work of the past would hopefully encourage reassessment of the reputations of senior generation artists and bring their contributions to the attention of younger generations. The introduction of this tax has discouraged me from including historic, secondary market work in my program. After all, if work of an earlier period has already fallen somewhat from popularity (albeit unfairly), clients are hardly inclined to pay an additional 5% for it.